Hello! I have made many declarations on this website in this part of the blog post before and followed up on very few of them, so who knows what’s going to happen. Life is strange, and full of surprises. But my current thinking is that I am going to attempt to write short and less-ambitious posts about individual games I am playing, and also to write them more frequently. Okay see you soon!

The Tower of Druaga has a reputation: famously opaque, obscure in the old, brutal way (not the subtle modern way, where an elegant trail of breadcrumbs leads to aesthetically precise secrets). The game was always described as linked intrinsically to the social dimension of Japanese arcade culture, the kind of collaboration only possible in a public setting. I’d heard of it, but as something that made a cameo in Jeremy Parish's videos, not like a game it was worth actually playing.

But I came across this list of game recommendations from the developer Sylvie the other day, upon which Druaga conspicuously appears…and curiosity got the better of me. There are a few versions, but the one I settled on was the Turbografx game, recently given a fan translation by Garrett Greenwalt.

The Tower of Druaga is simply and elegantly structured. You control Gil (short, wonderfully, for “Gilgamesh”). You are trying to get to the top floor to rescue your girlfriend (I think), Ki, who has been captured by the demon Druaga. Each floor is a level, each level is a maze, and each maze contains a secret or two, some monsters, a door to the next floor, and a key for the door.

The twist is that if you just get the key and open the door, at some point you will get stuck and become unable to progress. This is because, while most of these secrets are technically optional, a small handful are required to progress past certain chokepoints. More than anything else, the game is about finding these secrets.

What this means is that Druaga is actually something of a puzzle game. What’s tricky is the feeling that the terms of the puzzles go largely undefined. Sometimes all you have to do is kill the monsters, but more often the clues are esoteric: step on these mysterious circles on the floor in a particular order; hit the unbreakable external wall with your weapon; use a spell to turn the lights off for five seconds. This is where the social dimension of the game came in: allegedly, players of the original Japanese arcade version would leave a notebook tied to the arcade machine, filled with the handful of clues they'd been able to puzzle out.

It strikes me that Druaga's transition to home consoles probably came as something of a mixed blessing. On the one hand, players now had the time to experiment: it's hard to walk around a level bonking every wall or whatever when game-overs cost money. On the other hand, stripping the game from its social context (especially before the internet, I imagine) must have made collaboration harder.

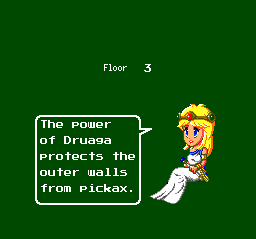

Enter the Turbografx version. There are a few tweaks this version makes, but the most essential one—the one that seems to me to transform the game entirely—is the addition of a hint at the beginning of each level. It's such a simple change, really: the kidnapped princess is given a single line of dialogue before each level begins.

Especially on the easier difficulties offered by the Turbografx edition, this change turns Druaga from being a hopelessly cryptic cypher to an energetic little puzzle game, a sequence of connected riddles. There's something really satisfying about how clear and discrete each level feels. The combat is enough to keep you on your toes, and the mazes themselves, while never approaching genuine difficulty, are both elegantly straightforward and just convoluted enough to add flavor to navigation.

It took a while for me to understand the game's idiosyncratic (and definitely older-school) terms. It was only after looking up what I was supposed to do a few times that I even realized I was actually getting hints—like, directly applicable hints. But with this in mind, the language of the game, while still occasionally frustratingly obtuse, clarifies. You start to realize, for example, that the weird circles on the floor of every level occasionally (though importantly not always) serve a mechanical function: you can sometimes unlock a secret by stepping on them in the right order, pausing on them for a set time, standing on them and swinging your sword. The specific attacks of enemies become relevant: one level's secret might require that you equip a fire-resist shield and resist five fire attacks, for example. Every aspect of the simple environment—the torches on the walls, the placement of the doorway—starts to glow with potential mechanical relevance.

It's a wonderful effect, one that winds up feeling surprisingly fresh, even contemporary, an expression of a recognizable but happily and imaginatively off-kilter puzzle game setup. (Another feature which nicely rhymes with modern indies was the length: it took me about four-and-a-half hours to beat on the easy mode, which gives unlimited lives.) Despite its substantial influence, Druaga wound up feeling to me like a transmission from a slightly alternate history, an oddball, wordy alternative to the adventure-game paradigm set by The Legend of Zelda, one which trades the original Zelda’s emphasis on the tricky and diffuse role-player’s pleasures of “immersion” and A Link to the Past's complexly interlocking dungeons for a satisfying sequence of problems. It feels like the kind of thing ripe for a System Erasure-esque modernist take on, if there isn't one already. There probably is! I'll let you know if I find it. Goodbye!