Greetings, dear readers! I hope you are doing well, or as well as can currently be done!

2024 was probably the first year of my life where I “kept up with new releases” in any aesthetic medium. The medium, of course, was VIDEO GAMES. It was pretty fun, if expensive, and intermittently unsatisfying; I beat fewer games than I usually do, which is fine, I guess, but also annoying. Frustrating, too, to miss many surely delightful entries, or to be exactly one hour into them. Still! It is always nice to have a project. In any case, my computer broke, so I am probably going to miss some of 2025’s shinier upcoming delights, but you know. There’s lots of stuff to do. Or so I’m told.

In any case, here are some of my favorites that came out last year. This will probably comprise a little series, unless I forget to write the other ones. See you later!

Dragon’s Dogma 2

This game is one of several from the year that feels like it exploded into consciousness and then disappeared. It sold hilariously well, considering it is a sequel to a famously off-kilter PS3 game; I don’t necessarily know why it dropped off the map, because I think it reviewed pretty well, too, and it seems, to me at least, like it kind of rules. Perhaps it was I who dropped off the map. It’s happened before (as you, dear reader, know better than anyone).

I like this game a lot. Some of this, perhaps too much of it, is because I like the idea of it. Capcom did some wacky stuff this year (more on Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess later), which I admire, and this game is deeply wacky. It feels meticulously crafted, even modern, in some regards (beautiful environments, many ways to approach things, a focus on “emergent gameplay”), but there are also, like, four enemy types, and you basically have to walk everywhere. The first mode of fast-travel that exists is this horse-drawn carriage situation, and more likely than not you’ll get mugged by a massive monster en route. I could not tell you a thing about the story, though I remember an elaborate stealth sequence culminating in a chat with a brothel mistress, or something? That was cool.

In any case, I am aware that this is not a compelling pitch. Nearly everyone I know who gave it a try hated it; it certainly takes a while to open up. But, for me at least, it did indeed began to add up to something strange and genuinely surprising: handsomely uncanny. Open-world exploration felt rewarding in a way it hadn’t for me since Elden Ring, and maybe never had before that.

But don’t go into it expecting anything like that, really. Most of the joy I derived from my 40 hours (I never completed it, unfortunately) in Dragons Dogma 2 emerged from a kind of very amused awe that this was a thing I could buy and play on my computer. You spend most of the game accompanied by “pawns” – custom-made NPCs (well, you make one pawn, and the rest are others’) who function as your party and say the same ten things over and over and over again. These absurdly obsequious, hilariously repetitive companions began to feel like a riff on the very idea of an RPG party – like, if the insight of the post-Final Fantasy IV JRPG is an understanding of the party as narrative engine and core, Dragon’s Dogma 2 is the opposite of that. It takes as its center the thing that’s unrealistic about any narrative where you’re the chosen one, and then builds this mythos and mechanical structure around that, one that feels somehow both profound and totally half-assed.

This is an overreading, I know, and it’s certainly not one which will convert any skeptics. Many have said it feels out of time in a funny way – the comparison point I most often hear is the PS3 (probably not incidentally, the first Dragon’s Dogma came out on PS3). It feels like the surreality and crunchiness of Dark Souls (sorry!!) extended laterally into the world itself. What is hard and rewarding about moving through Sen’s Fortress or whatever is now almost conceptually hard. It’s just a weird fucking time. I want to finish my playthrough, but I’ve heard the ending sucks, but this seems appropriate, somehow. The magic trick of making it so it owns when something sucks is probably evidence of a personal problem rather than a quality inherent to a work of art; however, smoke ’em, as I always say, if you got ’em. When you cook a steak in camp a video of a real life cooking steak plays, and when they asked the director why he said a real steak looks more realistic than an animated steak, and that’s why Dragons Dogma 2 is one of my favorite games of 2024.

Balatro

lol

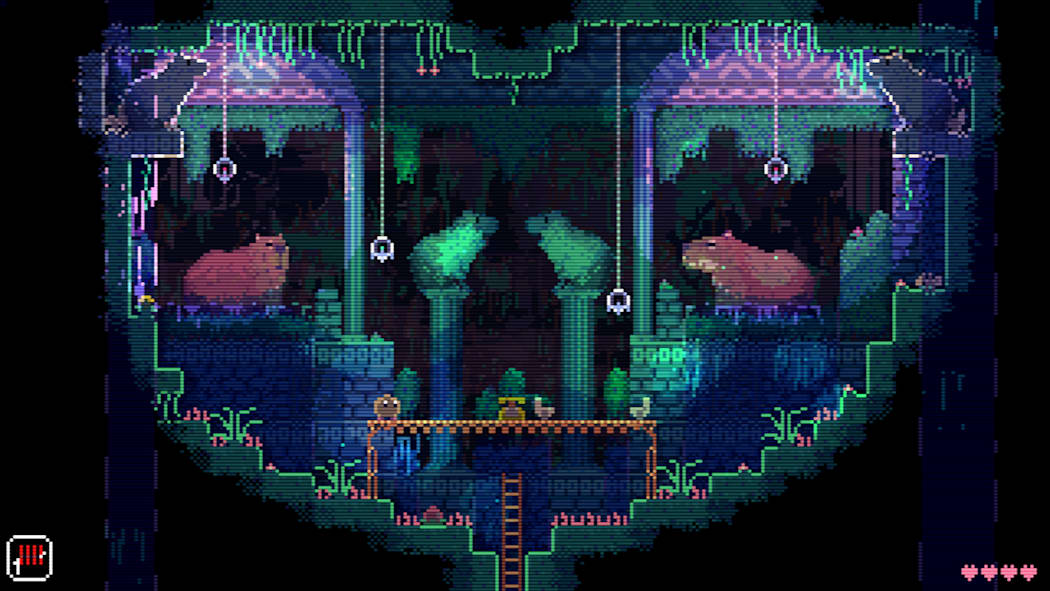

Animal Well

I’ve heard it said by a few different people (including someone on Friday: if you’re reading this, hello!) that a good puzzle game sort of tricks you into feeling smart—it leads you right up to the answer, way closer than you think you are, and then leaves just enough room for you to make the leap and receive a happy click of insight. By this metric, I think Animal Well is a great puzzle game. But there’s something else going on here, too. I was reminded while playing of this bit from designer Derek Yu’s book about the making of Spelunky (my actual game of the year of 2024, but more on that later), written by a judge describing Spelunky’s appeal:

With Spelunky, you are never learning a “piece” of music… It’s still a game about repetition and learning, but what you are learning is the overall composition, understanding the overall system and how it works, and becoming fluent in that [...] Spelunky looks like a game of execution, but it’s really a game about information and decision-making. How good are you at looking at a situation and understanding what it means? [...] You must rely on your literacy of the system, and this is a kind of holistic knowledge that feels great in my brain, a wonderful new flavor for a single-player game, and a deeply promising direction for further exploration.

One of the organizing premises of Spelunky (adopted from earlier roguelikes, as the book explains) is the idea that every object in the game follows the same rules as all the others. Everything can bump into everything else. A yeti can pick up and throw you just like you can pick up and throw a bomb. The altar on which you sacrifice incapacitated enemies (and allies) kills you if you find yourself incapacitated on it. The manic comedy of dying in Spelunky emerges from the sheer quantity of unanticipated outcomes a closed system with shockingly few variables can generate; the process of interpreting and negotiating endlessly new iterations of this system is both mechanically and cognitively satisfying.

Unlike Spelunky, Animal Well’s is world is thoroughly bespoke—it’s maybe the most meticulously, rigorously designed video game world I’ve ever engaged with. And to be sure, there’s a lot of carefully concealed hand-holding; you are closer at all times to the solutions than you feel yourself to be, and your sense that you are God’s biggest genius after you figure something out is certainly an illusion, if a happy one.

But the pleasure of Animal Well is related to Spelunky’s insofar as it both games cut you loose into a world which methodically teaches you how to interpret it. You’ll stumble into a corner that opens onto a secret passageway; and then you’ll step back and realize that the dangling vines did look a little off, didn’t they; and then when you return to an earlier room, you’ll notice that the vines look off in the same way, in a corner you haven’t explored.

This learning is in constant dialogue with the game’s progression, which consists almost exclusively in gaining new tools. You’ll face an obstacle a thousand times, laboriously learning to navigate your way around it, and then you’ll get an object that will let you bypass the obstacle entirely. The pacing of the game is as meticulous as anything else about it.

And the surprises! Really crazy stuff is constantly happening! When my mother visited me, I showed it to her because I figured she’d like how cool it looked; while her interest in video games is generally limited to Animal Crossing (though she very kindly indulges me when I babble about them), so much weird, surprising shit happened basically immediately that we wound up playing for a while and just cackling at everything. (Developers and marketers take note: if you’re trying to appeal to a wider demographic, try starting your game title with the word Animal.)

The pixel art is gorgeous, but it also serves the game’s fundamental design in a way I haven’t quite seen before: often the “tell” will be a difference of a pixel or two, in a way that feels both legible and subtle; a less rigorous aesthetic would not convey this balance as gracefully or satisfyingly. The geometry of the game is itself expressive in a way that draws out the player’s sense that they’re interacting with something not only built but built on purpose, according to a logic you can learn. It’s really good!