Hi! The part where I’m actually talking about the game starts at #6. The rest is more “meta” (ew) stuff that might or might not interest you. Okay, later!

A COUPLE OF NOTES ON TALKING ABOUT THE GAME

- Here is a warning: I am on board with 100% of the hype. Recency bias and all that, but this game feels like one of the best things I’ve ever played in my entire life. As a result, this letter runs the risk of feeling comically hyperbolic.

- So it is worth noting at the top that I do believe the consensus is somewhat deceptive, because it’s definitely a bristlier and more niche game than it lets on. It’s ultimately a roguelike, I think, which means that solving a puzzle intellectually does not mean you have the immediate capacity to implement that solution, which can be annoying. (More on stuff being annoying later.) It’s also a classic give it 20 hours/the game really starts after the credits type of game which, you know. I mean, it’s true—but you know. For my part, it took me fifteen or twenty hours to hit credits; I’ve now sunk about sixty hours into the game—not counting the time I’ve spent staring at notes and screenshots—and I don’t feel particularly close to being “done.”

- Why would the consensus be deceptive? In the most general terms, I think that Blue Prince is a game in a strange little sort-of-subgenre I am very fond of, one that is uniquely difficult to review. These are games where the process of discovering the mechanics is an intrinsic part of the game experience. Two games like this I think I’ve talked about here are Animal Well and Void Stranger (which is, as far as I can tell, maybe the closest spiritual relative to Blue Prince, though the experience and gameplay and overall vibes are very, very different); NieR: Automata is another, less severe example. In an important sense, it is a “spoiler” to describe how you literally play these games. But because the way a game works is an intrinsic part of whether or not it is “fun”—that is, because enjoying a game is (usually) beholden to whether or not you enjoy actually engaging in the mechanics—this means that a review which avoids properly describing a game in order to preserve the integrity of an experience cannot fully serve the function of guiding the consumer. And while guiding the consumer is a “lower” function than other kinds of review, maybe, given that they just announced that the new Mario Kart is gonna be eighty freaking smackeroos, I can’t but think it’s still kind of important. (Though will anyone not buy Mario Kart World because the reviews said it wasn’t good? In what world would the reviews even say that? Who knows! Not me.)

- I don’t have a solution to this! Nor does there necessarily need to be one, especially given the ease of returning a game on Steam or whatever. Maybe the only real lesson is the perennial one that Metacritic sucks and is bad; whatever the case, I think this problem is interesting. Luckily, I do not consider any of the information in any of these letters to be advice, because why on Earth would you take advice from someone like me, so it’s not my problem. Good luck!

IMPLICATION OF ABOVE NOTES

- In order to talk about Blue Prince meaningfully, there might be what you would consider spoilers in here. If you’re in early days with the game, enjoying it, and want to completely avoid these, ignore the e-mail, maybe. Or maybe not! I talk about it all in pretty broad terms—most of what I’m talking about is either basic mechanics or capable of being inferred from a handful of documents in rooms you’ll see in the first few hours of gameplay. (At least, I hope and think that’s the case!! Forgive me if it’s not!!!) But it’s worth noting I don’t think you should be too worried about leaving the experience 100% Perfectly Uncontaminated. There’s so much in the game that anything in here that could be a spoiler probably won’t make any sense anyway, and there are five thousand other things to learn in the meantime. I do talk about basic narrative stuff; and while I have only figured most of this out in the last dozen or so hours, this is not because it is gated in any particularly difficult or interesting way, but because I am stupid. Anyway, the video game:

BLUE PRINCE (2025)

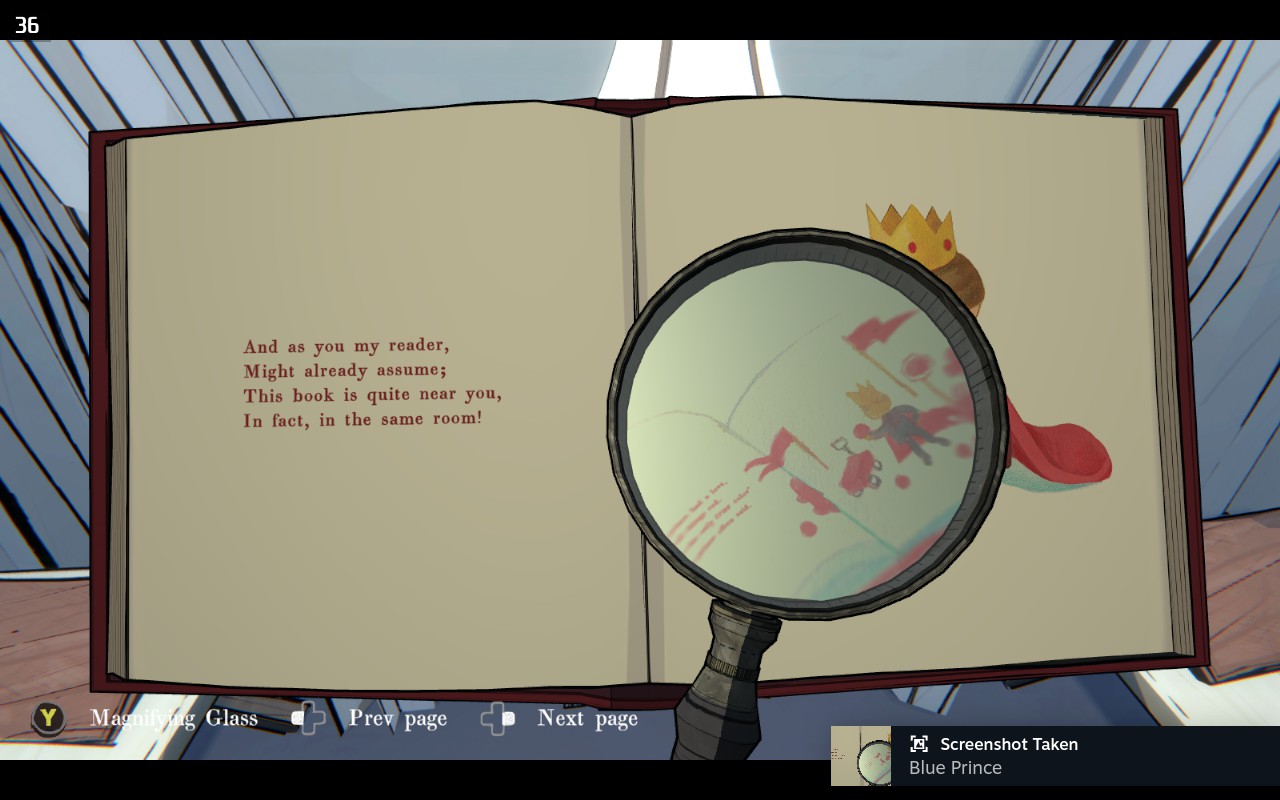

- Blue Prince thematizes the lonely, magical experience of single-player video games. It is about what is sorrowful and gorgeous in the experience of you and the strange glowing screen, the visual and physical interface which transmutes occulted and abstracted textual-numerical codes into a kind of private synesthetic reality. It’s a game about one person wandering empty hallways over and over again, but the deeper you go, the closer proximity you feel to the spirit of the creators and the world they’ve built. Each person’s progress through the game is, in my experience of talking to people about it, wildly different—your progress through Blue Prince will not be the same as anyone else’s, and this feels special and beautiful.

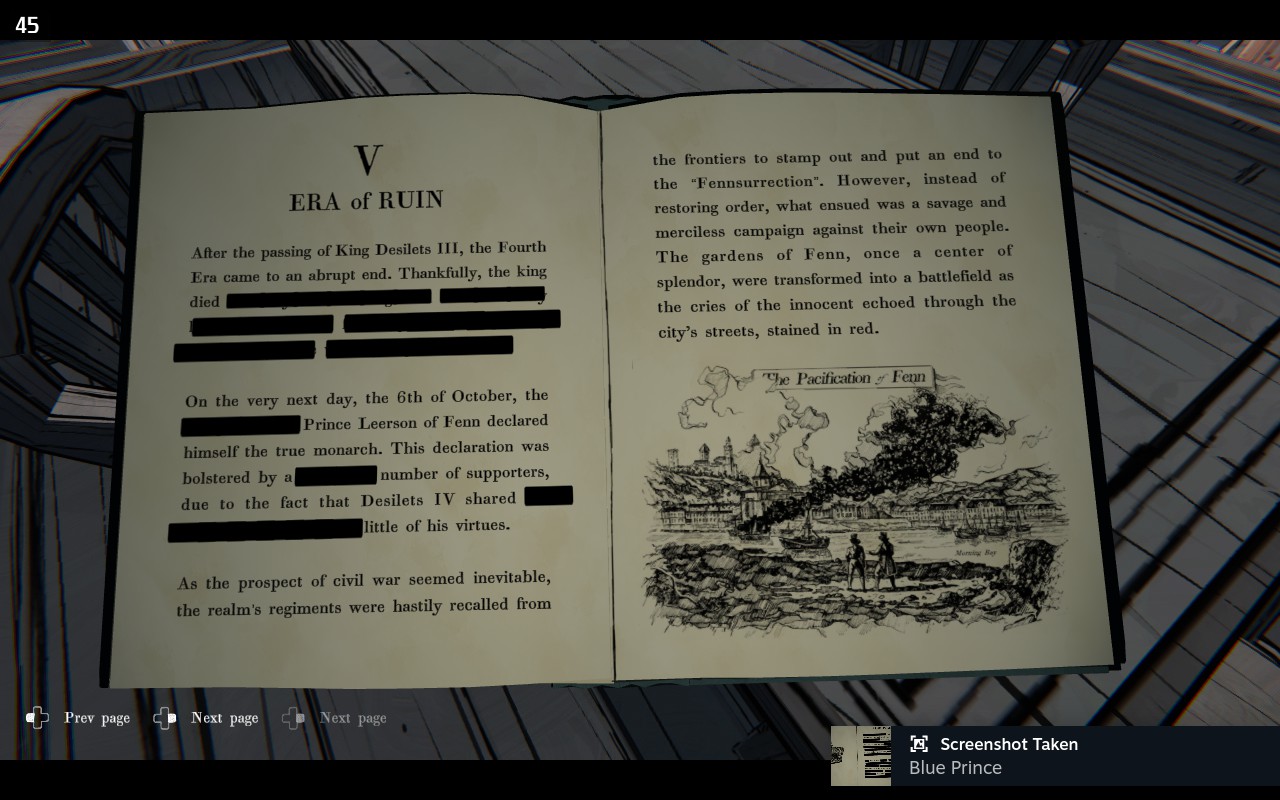

- Like Elden Ring, it is a game built around the sorrow and grandeur of ruins. It’s legitimately shocking how rich and well-realized and buried the narrative is. There’s a genuinely unbelievable level of confidence oozing from this game’s design. That the narrative you are uncovering happens to connect the pedagogical process by which you learn how to play a roguelike to the experience of sifting through the spiritual and material ruins of authoritarianism is extremely wild to me. (More on that soon.)

- It’s beautiful! It’s beautiful to look at. It’s beautiful to listen to. For a game obsessed with depth, the surfaces sure are beautiful. I’ve never seen video game art quite like it: the dark-outlined, almost cel-shaded shapes; the meticulously intricate maps and symbols. The sound design is minimal and accurate and thoroughly persuasive. The music is great. Great woodwind writing in particular. Sonorities, timbres, etc. It’s a very cohesive aesthetic vision. The spaces you’re in are good spaces to hang out in.

- Because I’ve wanted to talk with people about this game because it’s driving me insane (in a good way), I’ve wound up arguing on the internet about it way more than I usually do these days. Though I’m extremely careful to hedge all my comments, because I am very nice or whatever, it is a uniquely maddening game to argue about—and I’m sure it’s equally uniquely maddening on the other side of the argument, the “why does this thing everyone likes actually suck” side of it—because the complaints people have about it are complaints about the design decisions that not only make the game great to play, but serve as the backbone of what I feel to be the game’s genuine existential wisdom.

The most common complaint I’ve seen is that the randomized roguelike nature of the game does not allow you to solve the puzzles it seems to want you to solve. This is true; it does this. If I were more attached to conventional environmental puzzle games (though I’ve do enjoy them), or if I didn’t like roguelikes so much (though I’ve only been really into them for a few months), I would potentially be disappointed by this.

Blue Prince, I’d argue, is actually very well-balanced game. Like all good roguelikes, it feels, at first, like it’s all random. Unless you get the jetpack in Spelunky, you’ll never get to the end; unless you get materials for a specific build early in Slay the Spire, you’ll never get past Act 2. But like both of those games, the more you learn, the more you learn this isn’t true. Besides, like both of those games, runs are quick and easy to start over; unlike conventional roguelikes, Blue Prince is actually quite generous with its permanent upgrades.1 Your task feels impossible at first but it isn’t, and not for any twitch-skill reasons. It’s trying to teach you how to see something that was there all along.

In any case, Blue Prince is not a conventional puzzle game, though it has puzzles in it, and it builds on the legacy of puzzle games. It has the scaffolding and structure of a roguelike—is, I’d say, a roguelike. But it’s not a conventional roguelike, either. It’s a new kind of game, I’d say, one which uses the friction between the two genres it draws upon not merely to generate excitement and pleasure for the player—though it does do this—but in order to make a statement about the relationship between desire and reality.

- The game, like most games, frames itself as something to be beaten. The goal, established in the beginning, is to get to the secret room in the big house. When you get there, you win! This, like so much in the game, is intentionally deceptive, a carefully-laid red herring: a trick. But it’s not a mean trick, one that gets you for no reason. The game’s setup is a trick because the game is telling a story about the falsity of grand, dominating narratives; moreover, realizing that the game’s setup is a trick facilitates an epiphany, and the game wants you to have epiphanies, because it is also about the nature of epiphanies.

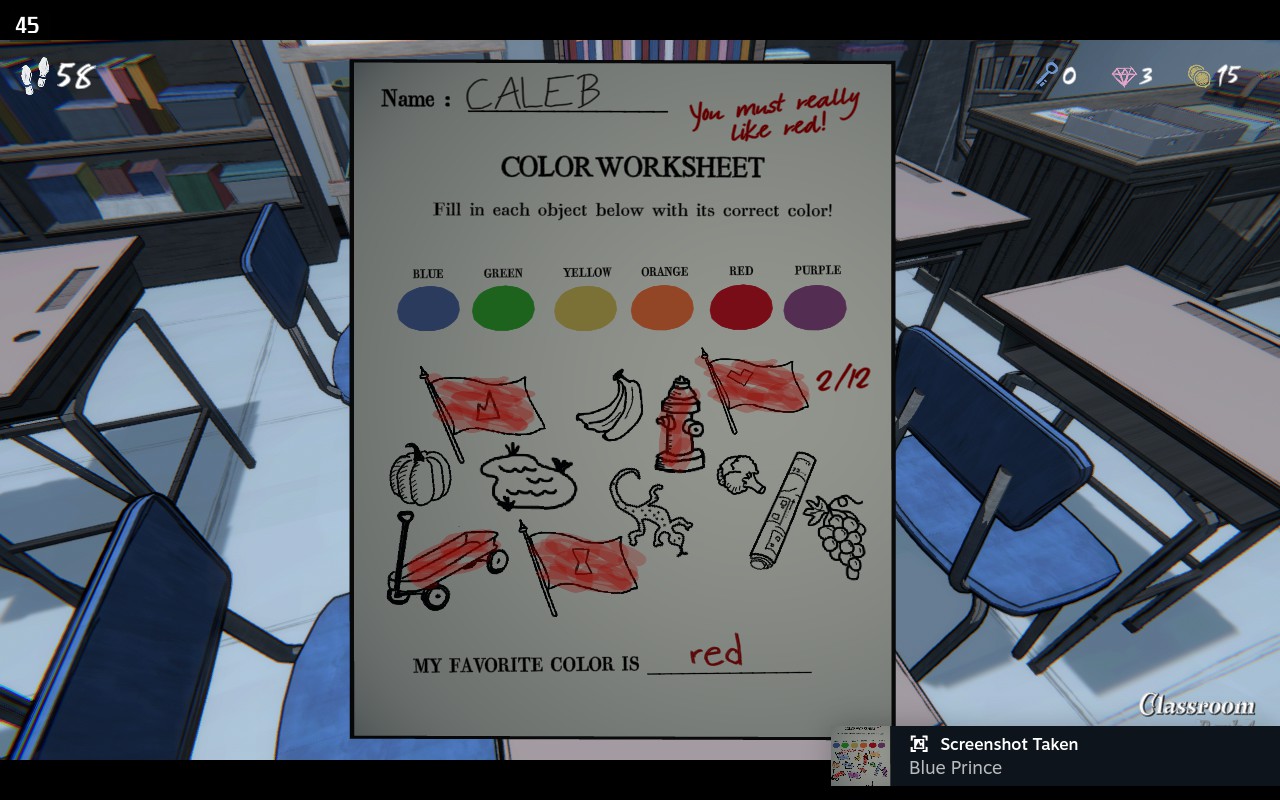

The game is tutorialized oddly—information often comes later than you’d expect. But the game will also just straight-up tell you the answers to puzzles if you wait long enough and keep poking around. It will instruct you, step-by-step, how to get places you’d like to get. Not everything, and not quickly, but it’ll give you so much. It is generous, but through a door you weren’t expecting. This, too, is on purpose, and of a piece with the broader design.

There are dozens and dozens of mysteries buried in Blue Prince; the miracle of the game is that they all fold back into the game’s essential unity. Each and every room has something to give you. And while it’s fun and satisfying to try to get to Room 46—and you have to pursue this goal in order to get to a lot of other stuff—it’s through the other mysteries offered by the game that it becomes genuinely profound.

What do we leave behind? The forces that purport to control reality would have us believe our legacies are nothing but expressions of allegiance or accidental testimonies to the futility of resistance. But this isn’t true. That the house is ephemeral, that each room and synergy and tool is a fleeting gift, and we don’t know when they’ll come back—this can be annoying and frustrating, sure. But it’s a necessary expression of the game’s central concerns: time, and loss, and repetition, and the tragic, beautiful endlessness of struggle. In a literal way, the game’s occasion is grief: the house is your inheritance, accessible to you only because the Baron has died. And there’s so much more to grieve that you, the player, will learn about as the game progresses. But what frustrates and brutalizes us about the passage of time—the flaw in the fabric of reality that gives us the most miserable, meaningless pain we will feel in our agonizingly short lives—is also what allows us the only chances we will ever have. These chances, too, are fleeting, impossible to grasp in ways that are often annoying, or disappointing, or devastating; but they are real. Time occasions grief, but it’s also why the future is unpredictable, and this unpredictability is the ground and foundation of all of our hope. Fascism is built on the nightmarish assumption of immortality—we can bring the past back, exactly as you remember it, better than ever, forever—but it can’t erase the unavoidable reality that there are surprises yet to come, and that no force on Earth, no matter how materially or ideologically powerful, can really, truly, perfectly predict the future. Maybe most of the surprises yet to come will be bad; maybe almost all of them will be. But some of them, hard as this can be to believe, won’t. We don’t know what we’ll learn in advance of when we learn it, and what we learn has the possibility to change our lives. We will turn some corner and a vista we hadn’t expected will present itself, bearing forth a grandeur that instantly becomes a part of us, for as long as we are here. It might even be true, really true, that what will survive of us is love.

Before you get mad at me—I mean, nobody here ever gets mad at me; thanks everyone—but before, for the first time ever, you get mad at me: I know this makes it more of a “roguelite” than a “roguelike.” I just don’t like looking at the word “roguelite” very much. Diet Roguelike. JV Roguelike? Blue Prince is kind of a Roguelike, Jr. ↩