One of the personal ironies of this "newsletter" is that I'm historically kind of reticent to talk about my tastes, at least in person. For example: it came to my attention recently that I had a reputation in college as someone who was mysterious and enigmatic about my interests. I learned this because a couple of years ago, I found out that a new friend had known before meeting me that I was someone who, a decade earlier, refused on principle to talk about what I was reading. This was funny not just because it forced me to remember that I had gone to college, though that is more "weird funny" than "haha funny," but also because I had been like that on purpose, and I thought I'd gotten away with it.

I don't think I was reticent because I was afraid that the stuff I liked was trashy, or pretentious, or whatever. I just didn't understand what liking things meant, or whether I was doing it right. I interacted with a lot of socially-minded people, people who had strong and interesting thoughts about American Culture and the State of Things, and I felt then, as I feel now, completely devoid of insight on that front. I have no idea what's going on, ever, and can be convinced of nearly anything. My sense of self is too vague, my experience too inchoate, to plant my feet in the whitewater of Takes and not fall over and bonk my head on a rock. How did you guys get all these opinions? Where did you find them? Are they right? Should I have them? I find myself invariably agreeing with the last person who spoke. In the years since, I have come better to understand why I appreciate the things I do, but at the time I felt that if I talked about something I was into I would probably be talked out of liking it, and that I'd ever liked it in the first place proved, for the nth time, that I had pink insulation fluff in my head instead of a brain. (More on that later.)

I’ve thought about this a lot since, and I’ve identified a few more hangups I’ve had over the years about the idea of aesthetic taste. Here is one: I am frightened by the thought of having particular taste, because I'm not sure, conceptually, how to draw the line between having a sensibility and unfairly wanting things to conform to my preconceptions. For a long time, this primarily manifested as a kind of existential sadness that I don't enjoy every object in the world exactly as much as their creators enjoyed them. That people create things is strange and sacred; it seems, on some level, like a disservice to what is holy in human experience not to appreciate them all equally. Each thing I disliked was an occasion for (a very small) grief, because it marked an impassible barricade between others and myself.

On some level I still believe this, I suppose, but I've come to a better understanding of the strange contingency of the creative process. For better and for worse, there are only a finite quantity of expressive forms; that someone cannot persuasively squeeze their experience into one or another has no bearing on the value of that experience. Art is a way of loving what is, of returning the world to itself, and there are lots of ways of doing that. Modes of expression that cannot be squeezed into one or another commodified aesthetic form are as, if not more, worthwhile than those which can. Communication isn’t always successful, but it’s certainly possible. (Concomitantly, things resonate or don’t with people for all sorts of reasons. Obviously this is like, “talking with other people 101”; but on the other hand, hast thou never taken with fear and trembling the aux cord, dreading the psychic decimation attendant upon an indifferent response to your beloved tunes?)

So. Another mostly bygone expression of this personal problem (and here we return to the insulation fluff) was my belief that if I enjoyed something, and someone else disliked it, I probably only enjoyed it because my head was, as I’d suspected, busted, and I should give up on everything and live in a box.

In any case, none of this shit should’ve really gotten to me, because so what if I had bad taste? What are the stakes? Oh no, you like something bad. You loser! I think it stressed me out so much for two reasons. For one, my brain was busted, but not like I thought. The other is that for the last decade-and-a-half or so, I have found myself invested, for reasons that elude me, in the prospect of creating something "good"—and how could I make something good if I couldn't tell the difference between bad and good?

I think recognizing the power of beholders to transform a work of art, to locate unique meaning within it, basically solves this problem. I didn't like something bad, because the thing wasn’t bad or good; I saw something good inside of the thing, a good someone else didn't see. (This doesn’t get all the way there for me—it’s missing something—but the concept of an objective good or bad misses more.)

This specific perplexity is one of the reasons I find myself interested in criticism in the first place. Writing is a means of inventing a language commensurate with subjective experience. I began writing this letter because I wanted to find a style suitable for explaining why certain cultural objects possess a hold on me—especially objects I never expected to be invested in. I wanted to find a way to talk about stuff I appreciated, stuff that might be weird or bad or dumb or silly in some ways, without falling into "guilty pleasure" style shame and justification, overdetermined 1960s-ish theories of high vs. low culture, clickbait-academic "actually x is Really Important, and here's why," etc. Those modes are well and good, sincerely, but they never quite capture what it is I find interesting in my experience of these things.

But—and this is probably my most recent problem on the taste front—does this mean negative criticism is bad? Isn’t that kind of positive-mindedness a concession to power? There’s rotten stuff out there, and doesn’t negative critical judgement not serve a necessary function in maintaining and sustaining the health of the cultural sphere? When trash reigns, oughtn't we hire a trash collector?

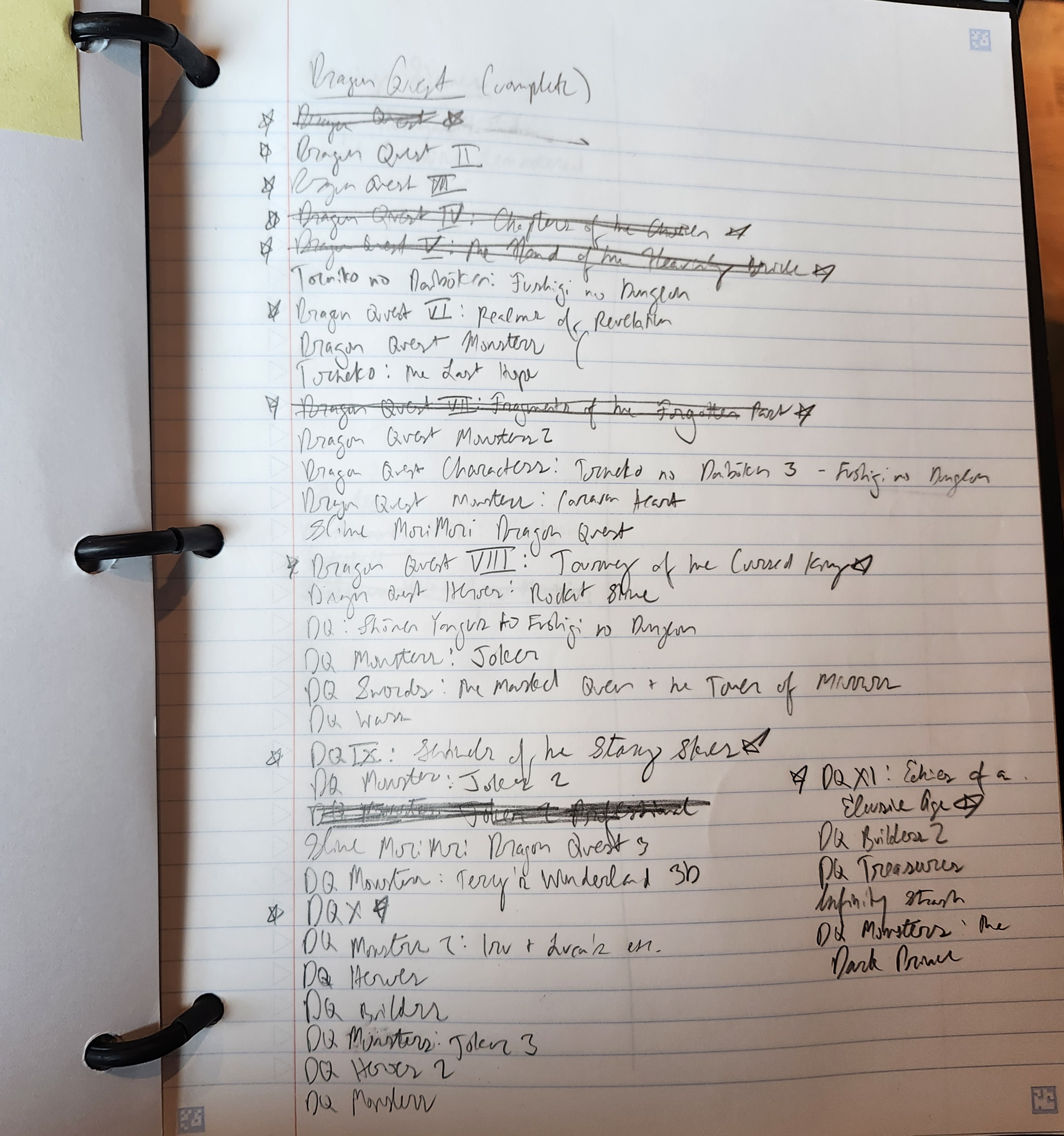

Look, man: I am a clinically depressed socialist living in the United States of America; of course doctrinaire positivity rubs me the wrong way. But I'm simply not usually confident enough in my my own negative judgements to really trust them. I love trash talk sometimes, sure, but most times I’ve tried to devote a letter to trash-talking, I’ll go back and read a couple positive reviews to test my argument, and it will feel like I’m missing something, like I should go back and review everything I’m mad at more closely, and then I have to, you know, add all those things to my Notebook Full of Lists of Media I Want to Get to Someday, and then three months have passed and I haven’t written another letter, and here we are.

In any case, realizing that what I thought was a cultural dilemma was merely a personal problem mostly dissolved this concern. (This is a useful theoretical maneuver, honestly, and I recommend giving it a try, especially if you post about things on the internet.) But my last letter, which was unusually negative (or at least ambivalent), got me interested in thinking about it all again. While I am predominantly interested in the phenomenon of "liking" (which, for the record, I understand even less than its negative), I am also interested, at least theoretically, in "disliking." What is happening when you don't like something? It is towards this end, dear reader, that we present the preliminary results of our investigation.

Seven Kinds of Disliking

It's been done before. This is interesting to me because it's probably the most context-dependent. Barring some sort of extreme and probably-unethical pedagogical experimentation, our personal encounters with art do not start at the chronological beginning of culture and move forward. Completionism is, strictly speaking, impossible. Moreover, saying something has been done before is always a matter of degree, not kind: everything references the past, but no one person is aware of the entire past. I suppose the clearest way of formulating this in ordinary language is when someone says something like, "it just makes me want to listen to [x]." It seems like x is trying to do y, when y already did y, and perfectly. The order in which someone in particular encounters things matters a lot here.

It's technically incompetent. This is a tricky one. 20th-century visual art and music in particular have done a lot to deepen and complicate our understanding of what "technical competence" is. A limited notion of technical competence will really limit your capacity to have the genuine good time available in, like, a modern art museum, or with a Ramones album. And people have also commented on the problem of a kind of general overcompetence: expressive, meaningful idiosyncrasies getting ironed out by means of technology and so on. But it's undeniably the case that I have disliked certain books because I feel like the writers aren't using the language very well. The noise outweighs the meaning; as in a cluttered room, I cannot find what I am looking for.

It doesn't cohere. If you held a gun to my head and told me to establish a single criterion for determining aesthetic quality objectively—well, hopefully I'd have both time and presence of mind to linger for a moment in awe of the places life can take a person—and then, assuming I could think of it in time, I'd say that the most important criterion for determining aesthetic quality was internal coherence. Does the thing hang together? There are many ways a thing can fail to hang together: the parts aren't made of the same stuff; the proportions are off; etc. Many of the other modes of disliking could be subsumed into this one, I think. I could write a lot more about this but I’d like to complete one of these stupid letters before December or whatever.

It evinces bigotry. This is probably both the most obvious and the most controversial kind of disliking. One can usually cast this criticism in terms of the others: a racist caricature can't be a good character in a novel, because one of the generally-accepted criteria for novelistic characters is the perception of psychological depth, and stereotyping flattens. Still, bigotry on its own is at least as valid a reason to dislike something as any of these others. Sometimes people think terrible things about whole types of people, and it’s rotten; the end.

The creator did something bad. Sometimes this doesn’t bug me, and sometimes it does. I distrust almost all general pronouncements on “the art and the artist” beyond that. It’s a matter of context and circumstance and our disastrous historical moment and previous disastrous historical moments and myriad specific qualities of the works of art in question and the many varieties of life experience and material conditions and blah blah blah so like, maybe don’t pay money to some Nazi black metal label or whatever, but beyond that I’ve got nothing for you. Good luck!

It's implausible. This is an interesting one. I guess I mean it in a couple of senses.

It violates its own sense of reality. "Realism" comes to mind, but it means a few too many things for it to be useful here. Hopefully obviously, I don't mean that something is bad when it violates the conventions of "literary realism," though there are people who do indeed dislike when these conventions are violated. What I mean is that "believability" is often, I think, another word for coherence. The end should feel as though it emerges from the same world as the beginning. Deus ex machina, etc.

The initial conditions are uninteresting/unpersuasive. This is a more subjective variation, but it's quite common, and I experience it a lot. I often struggle with dystopian fiction because adding more made-up bad things to the world, which has lots and lots of bad things in it already, often does not grab my interest. This is hardly a rule—what is a novel but a bunch of bad stuff someone made up for some reason—but you know. In practice, it happens.

It gives me nothing to hold onto. There's some overlap with 5b here. Still, I think this collects a few common objections.

I didn't like any of the characters (so to speak). The discourse about "likeability" has likely been rehearsed to death, and I've understood precisely none of it. I truly just don't know what people want. Which is fine! God loves us equally, even when we're clueless. I confess that this issue in particular sort of wigs me out—it's the need for an identificatory function that makes me fear that aesthetic taste is fundamentally solipsistic. But I've also had that nice feeling of being "seen" in some specific way by art, and I think that's obviously good, you know! Ultimately, I think the solution lies in the two-way nature of identification: identification not only connects the outside to you, but it connects you back to the outside. To see yourself in another is to see another in yourself. In any case, I think one of the things people mean when they say that "none of the characters in [book] were likeable" is that the work gave them no purchase or investment in its world; given that the novelistic tradition is deeply bound up in the exploration of psychology and character, liking a character is perhaps the most common way to get invested in a book.

It's boring. This is a good one. I know the word "interesting" gets a lot of flak, but it's one of my favorite critical terms, honestly, because it points to the thing that's really magical about art: it can pull your attention out of yourself, into a whole other thing. Another meaning of "interests" refers to things that benefit you: it's "in your best interest," etc. It is wonderful to me that a work of art can generate this! Anyway, stuff is boring when it doesn’t. Again, more to say here, but I’d like to get something written ever.

There are others, I’m sure, but this is a preliminary study. Blessings on you all! Bye!