Hello! This week I’m taking a close look at a couple of opening moments: John le Carré’s A Perfect Spy and Final Fantasy IV, and the way that environments in particular contribute to our understandings of characters. If these examples bore you, do not fear: I will hopefully take a look at some more recent games next week. As always, feel free to reach out if you have questions, comments, suggestions, complaints, etc.!

A literary character is, at root, a discrete set of utterances. (I’m using “utterances” instead of “sentences” to account for the fact that some stories and novels are more grammatically expansive, but 99% of the time they’re sentences.) In any given story, you could theoretically compile a list of times a character speaks, acts, or thinks; these, in sum, would comprise the character.

Most good stories are complex, so they triangulate this process: people not only speak, but are spoken of; they not only act, but are acted upon. (To say nothing of narrative modes like free indirect discourse, a mode which, among other things, blurs the edges between world and mind.) Whether or not the things the external world says and does constitute the character depends, in part, on how porous you think people’s boundaries are. I like thinking of people not as discrete units, but as parts of larger wholes; if you take this as a starting point, “character” becomes a much more expansive concept.

These thoughts came up for me in the course of reading the John le Carré novel A Perfect Spy, a book I wound up really enjoying. Here is the first sentence of A Perfect Spy:

In the small hours of a blustery October morning in a south Devon coastal town that seemed to have been deserted by its inhabitants, Magnus Pym got out of his elderly country taxi-cab and, having paid the driver and waited till he had left, struck out across the church square.

This is a classic lot-of-information first sentence. There’s a kind of gentle desolation to the opening clause—small hours; blustery morning; deserted town. It is lonely and solid. Syntactically, it’s a bit breathless, which I think contributes to the scene’s solidity; we’re given a neat pile of information (when, both in terms of day and year; where; what it feels like) and dropped into the middle of things, like one of those little street view guys from Google Maps. The structure of the sentence tugs us gently but firmly into the scene.

And while the reader doesn’t know this yet, this opening clause contains information that is crucial within the world of the book itself. The present-day action of the novel is almost entirely dedicated to the people trying to track our protagonist down. We’re immediately in the realm of dramatic irony.

We can see, too, how much from beyond the book comes into our understanding of the situation. “Small hours” is a phrase I don’t hear out loud that often; it strikes me as a bit old-fashioned, maybe more British English than American. “Blustery,” is a word, like the phrase “small hours,” that I wouldn’t exactly describe as “formal”—but it does strike me as playfully literary, maybe also old-fashioned. (I mostly think of Winnie-the-Pooh.) And then we of course have to know what October is, where Devon is; more generally, we need to know what mornings and coasts are. So there’s a lot going on here. (A functional definition of literary language is, I think, “language organized and intended to have a lot going on.”)

At nearly the exact halfway point of the sentence, we are introduced to the protagonist, the improbably named Magnus Pym. Visually, he is at the center of things; his name marks the point where the music of the sentence starts to resolve, the weight that begins to draw its rhythm to a close. (I would not call le Carré a particularly “musical” stylist—his writing is, I think, consciously prosaic and unobtrusive—but he has a lovely, understated rhythmic sensibility, one that’s operative at every scale: sentence, passage, section, chapter, and the overall book.)

“You’re telling me the spy…is perfect?” Le Carré continues (feel free to skim):

His destination was a terrace of ill-lit Victorian boardinghouses with names like Bel-a-Vista, The Commodore and Eureka. In build he was powerful but stately, a representative of something. His stride was agile, his body forward-sloping in the best tradition of the Anglo-Saxon administrative class. In the same attitude, whether static or in motion, Englishmen have hoisted flags over distant colonies, discovered the sources of great rivers, stood on the decks of sinking ships. He had been travelling in one way or another for sixteen hours but he wore no overcoat or hat. He carried a fat black briefcase of the official kind and in the other hand a green Harrods bag. A strong sea wind lashed at his city suit, salt rain stung his eyes, balls of spume skimmed across his path. Pym ignored them. Reaching the porch of a house marked "No Vacancies" he pressed the bell and waited, first for the outside light to go on, then for the chains to be unfastened from inside. While he waited a church clock began striking five. As if in answer to its summons Pym turned on his heel and stared back at the square. At the graceless tower of the Baptist church posturing against the racing clouds. At the writhing monkey-puzzle trees, pride of the ornamental gardens. At the empty bandstand. At the bus shelter. At the dark patches of the side streets. At the doorways one by one.

We get more here: his destination and accoutrements, the ironic (assuming, as we probably do, that Pym is the perfect spy referred to in the title) reference to his Englishness, a few actions which advance the plot. We see him looking around; we follow his keen eye around the town square. We are given a lot of information.

But for me, at least, the most effective bit of characterization happened at the beginning of the paragraph, with the simple act of describing the setting. The rest of the paragraph feels almost like a riff on that organizing image: an elucidation of the already-established fact that Magnus Pym is the kind of guy that would wind up here, in the kind of situation to bring him.

I have received the advice, regarding “creative” writing, to describe environments and settings not with the intent of providing a god’s-eye view of things, but in a way that reflects back on the characters and action. My first understanding of this sentiment was that we were supposed to render the writing a kind of projection: fiction, even the most detached third-person fiction, is always situated within a particular perspective; we should see the way the book’s organizing consciousness sees. (It is also an acknowledgement of the fact that centuries of literary tradition have trained to perceive setting not merely as literal, but also in a symbolic register.)

I think these ways of thinking about it are essentially correct. But I also think that this principle illustrates the fact that we are continuous with our environments. Character is, in a real sense, everything; which is to say that all storytelling is environmental. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

As is true of every kind of aesthetic object, there are many lenses through which we can approach video games; my approach here is not meant to be exhaustive. But I am interested, at least for the purposes of understanding video game characters, in thinking about video games first and foremost as works of narrative art.

I think this is a more expansive lens than it might seem. When people talk about a game’s “story,” they often are talking about the aspects which resemble other forms of narrative media, especially cutscenes and dialogue. The interactive counterpart of this is often cast under the umbrella term “environmental storytelling” — the conveyance of narrative information by means of, among other things, setting and objects. (For example, the narratives of games like Dark Souls and Bloodborne are often conveyed primarily by way of item descriptions.)

I’ve read people about emergent gameplay, including “emergent narrative”; raiding in World of Warcraft taught me that every video game experience has a story—even your fiftieth time through the extraordinarily dull Molten Core raid dungeon; even the “meta” experience of being in a guild. (These might not be good stories, but, in my experience, a story definitely emerges.) The emergent angle is useful in a lot of ways, but I’m curious about what a still more holistic view of all of this would look like.

When you’re actually playing a video game, every dimension of the game contributes to the story, even (especially) when you aren’t consciously noticing them. What, then, are the formal features of video games which contribute to our experience of a given character? As with fiction, the answer is different from story to story; I’d like to start with the opening of an influential and clear example of early-ish JRPG storytelling: Final Fantasy IV.

(For what it’s worth, I’m far from the first to comment on these features of FFIV— Jeremy Parish’s excellent series on the game is a great, in-depth exploration of these questions, including late game mechanics-as-narrative innovations I don’t have space to explore here. I’m just laying this all out as a kind of foundation.)

Final Fantasy IV was the first Final Fantasy game released on the Super Famicom; it was the second in the series translated to English. It is not the first narrative-heavy game in the series—Final Fantasy II and III also had relatively detailed stories, pre-written characters with backstories and a rotating party of guests—but it is by far the most ambitious, as well as the first, in my opinion, to really achieve the kind of aesthetic unity I’m interested in discussing here.

FFIV starts in medias res, with our protagonist Cecil and his crew en route to...somewhere.1

There’s a lot going on already:

We can infer a number of facts from the design details, especially if we have the rest of the series in mind:

We already have access to an airship, which we usually don’t get until later in the game. As will be reinforced later, we’re unexpectedly powerful for the beginning of the game.

The ship is heavily armed. It’s got those chill little cannons.

The dialogue explains Cecil is the captain, but he’s visually differentiated, too — he’s the only one in dark armor. Besides the ostensibly metal cannons, his uniform is the visually darkest entity on the screen. If we’re familiar with the dark magic/light magic symbology of the past games — or of basically any Western or Western-influenced fantasy media — we have an intuitive sense for what this means.

Even more basically, the flying pirate-style ship shows us something we probably already know about the game’s genre: it’s not going to be “realistic.”

The cutscene assumes a top-down perspective identical, as we will learn, with non-combat gameplay. The relevant parallel here, I think, is theatrical production. As I mentioned in my Final Fantasy VI write-up, Takashi Tokita, the lead game designer and scenario writer on FFIV, has a background in theater; given that there are not many opportunities in games like FFIV for technical gestures like expressive camera work, the game instead relies on the trappings of stage productions: set and costume design, blocking, and spoken dialogue.

The game’s technical constraints also provide an analogue for one of the difficulties of larger theatrical productions: namely, that the audience can be pretty far away from the stage. Character designers and actors alike have to find an expressive gestural and physical mode that will reach, respectively, the couch or the back row.

The visual (and aural) composition is identical when the player controls a character as when, like here, we’re powerlessly watching the characters act. The action button, used to select menu items and interact with objects, is also used to advance dialogue during these scenes. Video games are uniquely tactile entities; I don’t think it’s trivial that we unconsciously recognize that, even when we’re not making things happen, we’re moving things along.

This is a long-winded way of getting to a fairly simple and intuitive point: namely, that a consistent means of presentation immerses us in the story, drawing us closer to, among other things, Cecil’s psychology. In the same way that the scene-setting first sentence of A Perfect Spy tells us something about Magnus and his world, these moments themselves provide a great deal of narrative information.

The next thing Cecil does is kill some dudes for their magic crystal:

- The glassy ground, the strange yellow color, the throne (behind the dialogue box), etc. — we’re in some kind of inner sanctum.

- In combat, an enemy’s death is signified by their sprite flickering and disappearing; roughly the same thing happens when enemies die from the top-down vantage.

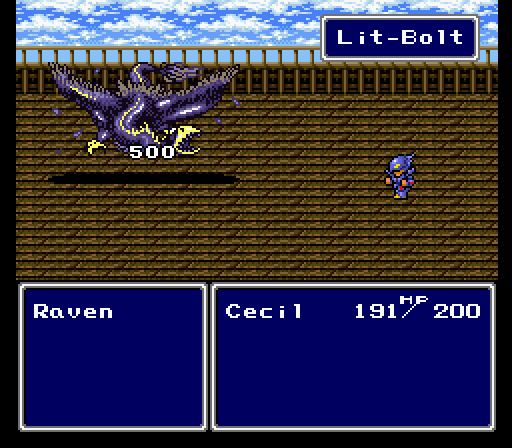

And so on. On the way back, Cecil has some doubts about what he’s done (the first hint that something more politically complicated is going on), and we get in some fights. The player is not yet controlling Cecil, but they probably recognize that this is a combat interface:

- Cecil is here doing more than twice as much damage as he has HP: he is, at this point, disproportionately powerful; it will take a while before the player is capable of doing as much damage as Cecil does here.

- Physically, the enemy sprites are much larger than Cecil’s. This continues throughout the game, and supports the feeling of constantly surmounting difficult odds.

- He’s facing them alone — his solitude, even amidst others, is a recurring theme.

It’s not that the interface is diegetic—we’re not led to believe that Cecil is actually fighting by means of selecting choices in a menu. But the formal consistency makes transitions between cutscene and player-controlled sections much more fluid. What happens when we’re not in control is the same kind of thing as what happens when we’re in control. The world is continuous, even if our agency isn’t. (Which, honestly, feels pretty accurate to my experience of things; again, though, that’s a story for another time.)

In any case — all I’ve tried to demonstrate is just how much of the design contributes to the narrative, including the characters. I’d hoped to get further into the intro of FFIV, which, for all the game’s datedness and faults, remains a fascinating and forward-thinking example of how to begin a game in medias res while also “onboarding” (sorry) players. In any case —

To be continued…

I took some screenshots of the opening in the recent “pixel remaster,” but I forgot to change the shitty font, and it irritated me, and it also made more sense to include images from the original. These images, from the original SNES version, have been borrowed from Mega64's Let's Play. ↩